Fifty years after Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk on the moon, Boundless looks back at the space race that led to this iconic lunar feat

As the 50th anniversary of the first moon manned landing approaches, join our special commemorative event at the National Space Centre.

Space travel has waxed and waned since the 1950s, but our fascination with it remains fixed. The moment of Neil Armstrong historic steps on the moon’s Sea of Tranquillity in July 1969 – now immortalised on the silver screen – marked a high-water mark in our exploration of the cosmos. Six hundred million people, almost a fifth of the world’s population at the time, watched the event live on television and, like the Kennedy assassination, the question ‘where were you when…’ remains evocatively linked to this singular triumph of human ingenuity.

The politics of the space race

John F Kennedy inspects ‘Friendship 7’ at Cape Canaveral.

Apollo 11 has long been viewed as a victory for freedom, for science and technology and for revealing the true insignificance of our earthly squabbles, but the reality was tightly rooted in the harsh geopolitics of its day. Even the choice of Armstrong to be ‘first’ owed much to changing fortunes and being in the right place at the right time.

In the 1960s, the United States and the Soviet Union were gripped by the most bitter freeze of the Cold War, their ideological rivalry having crystallised into building missiles capable of travelling thousands of miles to attack each other’s cities. The Soviets were first to successfully test such a missile and used it repeatedly, not as a bringer of carnage, but rather to establish technological might: launching the world’s first artificial satellite, sending a probe to the moon and putting the first man into space.

Back on Earth, America’s efforts to help Cuban refugees overthrow the Soviet-backed dictator Fidel Castro backfired dismally and a frustrated President John F Kennedy sought any means to catapult the United States out of second place behind Russia.

How the space race began

Neil Armstong performs lunar module simulations.

A manned journey to the moon offered Kennedy the solution he needed, and in May 1961 he proposed a national goal to get there “before this decade is out”. NASA’s Apollo spacecraft and giant Saturn V rocket were ideally suited for the challenge, but the Soviets also had the moon in their sights as their own N1 booster took shape. A ‘space race’ thus ignited, but the much-publicised successes of spacewalking, rendezvous and docking were cruelly juxtaposed with tragedy as astronauts and cosmonauts lost their lives in aircraft accidents, spacecraft fires and catastrophic parachute failures.

Inspired by the space race? Discover the best space-themed days out in the UK

One astronaut who came within a hair’s breadth of premature death was Armstrong himself. In March 1966, he and Gemini 8 crewmate Dave Scott were meant to dock in space with an Agena target vehicle.

They succeeded, but a stuck-on thruster sent them into an uncontrollable spin. As their vision began to blur, and scarcely able to read their instruments, the astronauts only survived by separating from the Agena and making an emergency return to Earth. Armstrong’s coolness and previous experience flying the X-15 rocket aircraft to the edge of space cannot have harmed his chances of gaining a seat on a moon mission. But the cards of fate still had other hands to play.

The first card fell in May 1968, when he narrowly escaped death again after ejecting from the lunar landing research vehicle, an ungainly and highly dangerous training aircraft. Three months later, Armstrong was serving as backup commander of Apollo 9. Under an unwritten crew-rotation rule, backup crews for a given mission usually skipped the next two flights, then became ‘prime crew’ for the third, meaning Armstrong might command Apollo 12, offering him a shot at the first lunar landing.

But that August, intelligence reports hinted that the Soviets were about to test-fly their N1 rocket and an anxious NASA hurriedly switched the flight order. Apollo 9 became Apollo 8 and flew to the moon in December.

Apollo 11

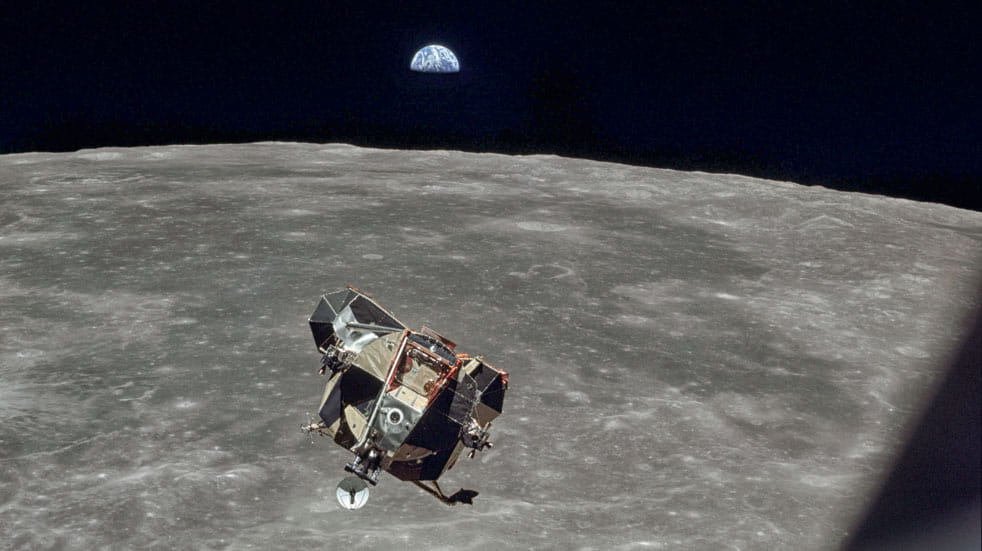

Apollo 11’s lunar module approaches to rendezvous with the Apollo command module after a 22-hour stay on the moon.

With the Soviet challenge thus beaten off, in January 1969 Armstrong was appointed to command Apollo 11, which grew likelier by the day to become the first lunar landing. America’s chances brightened in February, when the first N1 rocket exploded seconds after lift-off. But still nothing was set in stone. Not until the spidery lunar module had been test-flown in March and a dress rehearsal performed in lunar orbit in May could a landing seriously be contemplated.

For his part, Armstrong refused to be drawn on whether Apollo 11 would be first to land on the moon, much less if he would make the first historic steps. Crewmate Mike Collins would remain in lunar orbit, while Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin descended to the surface. On earlier Gemini flights, the co-pilot – not the commander – went outside and it’s claimed that Aldrin actively lobbied that he should be first.

Find out more about the UK's aerial history to celebrate 100 years of the Royal Air Force

But the Gemini precedent did not apply for, as historian Andrew Chaikin remarked, Apollo 11 would not be in flight after landing on the moon; it would be in port. And after coming to port, as every naval officer knows, the skipper is always first off the ship.

The solution turned out to be a pragmatic one. Months of training revealed the inherent difficulty of donning bulky space suits in the lunar module’s broom cupboard-sized cabin. Its square hatch opened towards the right-hand side – against Aldrin – which required him to stand back into his corner, so that Armstrong could get down on hands and knees, crawl backwards onto a tiny porch, then amble his way down a nine-rung ladder to the surface. For Aldrin to go first, they’d need to swap places and risk damaging their suits or knocking switches or circuit breakers. It was a moot decision.

First men on the moon

Buzz Aldrin in the lunar module during the Apollo 11 mission.

Fifty midsummers ago, these two men became the first to experience the peculiar one-sixth gravitational tug of the moon on their bodies. Armstrong and Aldrin spent a couple of hours awkwardly traversing the powdery surface, loping from foot to foot one minute, hopping like kangaroos the next. The desolate stillness of the moon captivated them, as did the visual clarity afforded by the almost complete lack of atmosphere.

And perhaps somewhere along the way, Neil Armstrong had the chance to reflect that, rather like the moon itself, his life’s journey had waxed and waned on its way to sending an ordinary man from America’s Midwest to a quite extraordinary place.

Returning to the moon

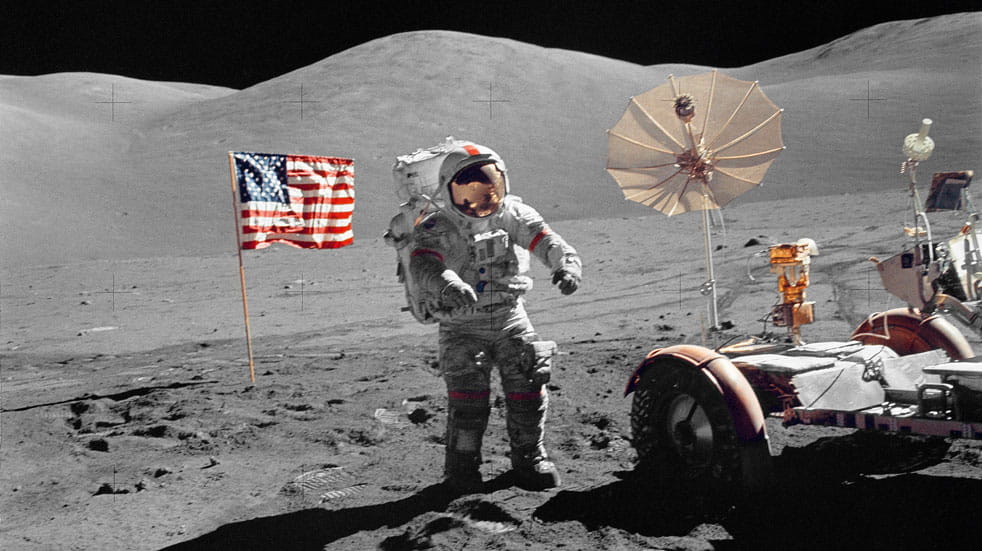

Eugene Cernan pictured in 1972 during the final Apollo lunar landing mission.

After Armstrong and Aldrin, five more teams of astronauts alighted on the moon, before Apollo 17 in December 1972 ended lunar exploration for the remainder of the 20th century. The cost, complexity and inherent risk was so high that three final Apollos – for which hardware had already been built – were unceremoniously scrapped. Years later, several managers and engineers responsible for those cancellations openly admitted that they should have fought harder to keep them.

Grand presidential initiatives – from George HW Bush’s Space Exploration Initiative to George W Bush’s Vision for Space Exploration – have come and gone, but there is an increasing appetite from several international players, including Europe, Japan and China, to establish permanent bases at the lunar south pole by the mid-2030s.

Join the anniversary celebrations

Find out more about our unique 50th anniversary celebration event at the National Space Centre in Leicester.

The race to Tranquillity

- April 1961– Russia launches the first man, Yuri Gagarin, into space.

- May 1971 – President John F Kennedy proposes the Lunar goal

- March 1965 – Russia performs the world’s first spacewalk

- August 1965 – Americans spend 8 days in space – equivalent to a return trip to the moon – in Gemini V

- March 1966 – America performs first rendezvous and docking in space

- January 1967 – Three US astronauts killed in Apollo 1 command module fire during training

- November 1967 – America’s first Saturn V rocket is successfully test-flown

- September 1968 – Russia’s Zond 5 launches animals into lunar orbit

- December 1968 – America’s Apollo 8 sends astronauts into lunar orbit

- July 1969 – America’s Apollo 11 achieves the first manned lunar landing