The most serene spot in the UK lies somewhere in the north-east – take a drive to discover it for yourself

The peace and quiet found close to Hadrian’s Wall makes this stretch of road one of our 50 favourite drives in the UK.

Halfway up a private track in the dead of night, surrounded by a thick forest of Christmas trees, we kill the main beams and creep forwards in the blackness. Backlit by a creamy moon, clouds blow around the sky like bonfire smoke. Out of the mist looms a timber battleship, unlit and silent, turrets slowly turning. Or is it the larch-wood shell of the Kielder Observatory and its rotating telescopes? It’s late. Who knows?

All of a sudden, the cloud smokescreen is chased away, revealing a cluster of stars so bright it’s like looking at the splayed end of a fibre-optic cable. We’re deep in the Northumberland International Dark Sky Park, one of the best places in the world to see into space, and about as tranquil a place as you could imagine.

In fact, somewhere near here, sandwiched between Scotland to the north and Hadrian’s Wall to the south, lies a top-secret patch of peat bog said to be the most tranquil spot in the whole of England. Tranquil because it’s miles from any road, pylon, dwelling or artificial light, and to reach it you must squelch, ankle-deep, through a midge-infested quagmire. And top-secret because, well, if everyone knew exactly where it was, it wouldn’t be so tranquil after all.

The route to peace and quiet

We set off up the A1 on a Monday morning, which is never going to be the most soothing experience, although our denim-blue V60 takes the edge off it somewhat. We’ve borrowed a D3 – that’s Volvo’s code for a 2.0-litre, 150hp diesel engine – with an eight-speed automatic gearbox and settle into an easy-going cruise, our ears entertained by the Bowers & Wilkins stereo (a whopping £2,500 extra but a worthy indulgence), which among other things can replicate the world-famous acoustics of Gothenburg Concert Hall in Volvo’s hometown, complete with spooky reverb.

Just past Newcastle, just about where England tapers to its narrowest point, we turn left on the A69. After a while, and roughly halfway to the west coast, we park near the ruins of Housesteads Roman Fort on Hadrian’s Wall, the ancient frontier of the Roman Empire. A walk in the drizzle takes us up a steep escarpment where we peer over the nearly 2,000-year-old stone barrier. Beyond it – then, as now – lies a rumpled duvet of moorland, uninhabited except for a few brave sheep nibbling on fountain-like tussocks. Somewhere out there is what we’ve come for – our little oasis of tranquillity.

The spot was identified by the Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE), whose colourful ‘tranquillity maps’ define areas of the country by their relative peace and quiet, varying from red hotspots for busy cities to dark-green splodges for remote countryside. And you don’t get much greener than Kielder Forest and the surrounding bogs, where the peat can be as much as 15 metres thick. Consider this: Kielder Water, the largest artificial lake in Britain by volume, has 27 miles of shoreline, is up to 52 metres deep and took two years to fill.

Yet the nearby mires hold more water than the lake itself. In other words, the whole place is an enormous bath sponge.The ground doesn’t just absorb moisture. The squishy moss soaks up sound too, acting like a giant shag-pile carpet, and this eerie quietude is an important factor in its tranquillity score. But a lack of noise and people isn’t the only consideration. The CPRE’s tranquillity map divides England into a grid of 500m by 500m squares, with each square given a score based on 42 different factors such as lines of sight to manmade objects, proximity to flightpaths and the clarity of the night sky. The idea is not only to quantify tranquillity, but to have it officially recognised, monitored and protected.

Check out more of our great drives:

Explore the mountains, valleys and Roman roads of the Lake District

Take your electric car on one of the best road trips in the UK and Europe

Discover our 50 favourite drives in the UK

The cost of tranquility

Which is why the exact whereabouts of the most tranquil spot remains appropriately hush-hush, and why we decided not to go rambling around trying to find it. That, plus the fact it looked like a hell of a trudge – a suspicion confirmed by Trevor Cox, Professor of Acoustic Engineering at the University of Salford, who persuaded the CPRE to give him the precise co-ordinates in the name of academic research. “The ground was very uneven, and my feet kept disappearing into dips and gullies and getting soaked,” he says in his book Sonic Wonderland: A Scientific Odyssey of Sound.

Damp and exhausted, he finally arrived. “It really was incredibly quiet,” he says, “with the only sound coming from my pounding heart, heavy breathing and the rhythmic squelching from my boots”. He then turned on his sound recorder. “There was nothing to be captured, apart from the dull background hiss of electrical noise from within the equipment, and the occasional flapping sound as I tried to kill the midges that were feasting on me.”

Was it worth the effort? That depends on what tranquillity means to you. “Complete silence in a natural setting is not necessarily wonderful,” says Professor Cox. “I wanted to hear birds or the trickle of a stream; even a buzzing fly would have been good – some sound that signified life.”

Back in the car, we loop around the impenetrable mires and into the woods on the other side. What had looked on the map like narrow lanes or tracks turn out to be glossy tarmac roads with long passing places – a sign that Kielder is a working forest with a constant flow of logging trucks. Fiddling with the V60’s settings on the central touchscreen, we find Sport mode, which livens things up a bit.

Buckled up in our bubble of serenity, we drive among the Sitka spruces and rejoin the only main road running through the forest. To the north, Kielder itself, which has been called the most remote village in England, and who are we to disbelieve them – to the south, our eventual lodgings for the evening at Tarset Tor Bunkhouse and Bothies. Half-expecting to spend the night in a brick shed, we’re pleasantly surprised to discover the bothies are in fact two-storey eco lodges on a hillside overlooking a river valley.

They were built by Rob Cocker, whose father was one of thousands of workers who came here in the 1970s to build the dam that made the reservoir. “He ended up buying the local pub,” says Rob. “The old landlady didn’t fancy the influx of navvies, so she gave him the keys and left.”

Originally intended for backpackers, Rob’s bunkhouse and bothies, which he runs with his wife Claire, now get more trade from families, forestry workers – a group of Canadian tree-planters visits every year – and stargazers who venture up to the observatory for its nightly, ticket-only events. And that’s exactly where we head next.

Driving in the dark

Did you know it takes half an hour or more for the human eye to fully adjust to darkness? Which is why we creep up the forest track using only sidelights and the faint, silvery moon-glow to find the edges of the private road. (Fear not, more organised people arrive earlier to avoid this problem, and other traffic was held back until we arrived).

Opened in 2008, five years before the area was officially declared a Dark Sky Park (the largest in Europe and one of the largest in the world, believe it or not), the observatory juts out from Black Fell like a wooden pier on concrete supports. Since completion it has won architectural prizes – it’s as if Kevin McCloud might wander by at any moment, delivering some monologue to a sweeping boom camera – and hosted over 25,000 visitors a year, all attracted by the pristine expanse of night sky above these tranquil borderlands.

They, like us, may never stand on that hallowed square of peat bog just a few miles away. They will, however, have dry boots and fewer midges to worry about, as well as a front-seat view of the universe, which – when it comes to tranquillity – is just as important as any natural landscape, if indeed such a thing actually exists.

Take Kielder, for example. For all its beauty, the entire area is actually a product of human activity – the forest is an industrial plantation; the lake was created to serve old shipyards. In fact, the only scene untouched by humankind is the one above our heads. For the night sky, as far as we know, is still just as nature intended. And thank heavens for that.

Northumberland travel tip

For one of the best views in the area, follow the A68 to the England/Scotland border at Carter Bar, high in the Cheviot Hills.

Kielder Observatory

Staffed by a team of ten astro experts, Kielder Observatory (kielderobservatory.org) is perhaps the best place in the UK to learn about the night sky and see it with your own eyes. There’s an event almost every night, except for four days around Christmas, and there’s something for everyone, from families and junior astronomers to seasoned stargazers. It’s extremely popular, so you absolutely must book in advance through the observatory’s website before turning up. The observatory only opens for evening events, though in the daytime you can walk up the track to see it from the outside and take in the views over the surrounding countryside and towards Kielder Water.

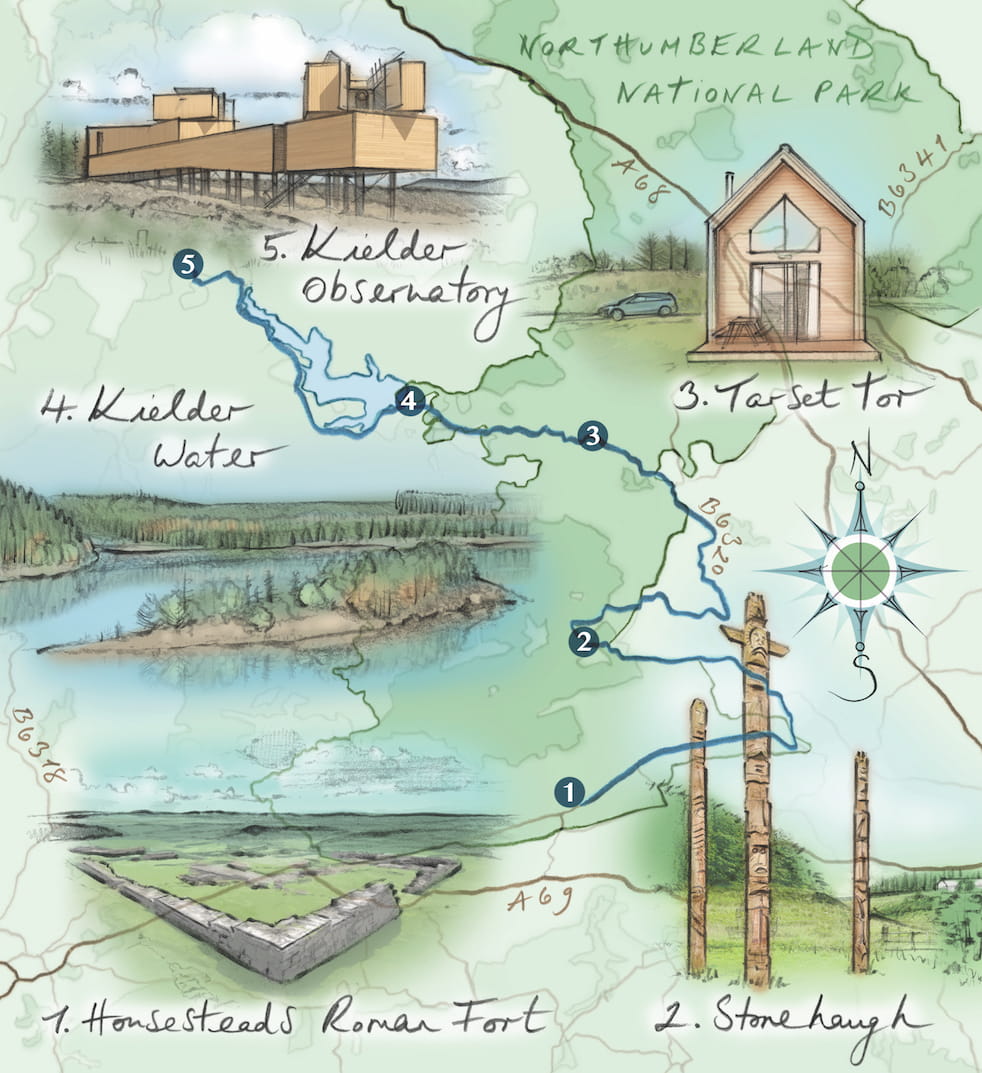

Route highlights

-

Housesteads Roman Fort: The most complete Roman fort in Britain, right in the middle of Hadrian’s Wall.

-

Stonehaugh: A forestry workers’ village built deep in the woods in the 1950s, which is also home to a collection of totem poles.

-

Tarset Tor: The upmarket eco bunkhouses and lodges where we stayed on our trip. Owner Rob reckons the property is exactly equidistant between the coasts.

-

Kielder Water: A recreational hotspot with all sorts to do, from waterskiing to paddleboarding. Keep an eye out for the nesting ospreys.

-

Kielder Observatory: Runs nightly stargazing and educational events, whatever the weather. Book in advance.

Where to stay: three of Kielder’s best bases for stargazers

-

Twenty Seven B&B: A former forestry worker’s house in Kielder village, Twenty Seven is the closest accommodation to the observatory (2.4 miles away up a forest track) with two en-suite rooms, two rooms with a shared bathroom, and an outdoor deck with telescopes for on-site stargazing.

-

Hesleyside Huts: Galactic glamping in luxury shepherd’s huts nestled in an oak copse within private parkland, complete with wood-burning stoves, ovens and hotplates, en-suite bathrooms, hot showers and outdoor firepits – one even has a four-poster bed while another has a roll-top copper bath.

-

Tarset Tor: Eco-friendly, self-catering accommodation on the edge of Kielder Forest. The three ‘bothies’ are two-bedroom lodges with four bunks per room, while the stylish bunkhouse is split into several four-bed rooms which can be booked separately or together.

-

Beacon Hill: Located on a family farm just outside of Northumberland National Park near Morpeth, Beacon Hill has 15 beautiful holiday cottages, a swimming pool and spa, and most importantly, its very own observatory with a powerful telescope.

Save 5% when you book unique stays with Hoseasons

Why not have your own stargazing adventure in the UK or Europe? Hoseasons has a whole range of accommodation including luxury lodges with hot tubs, deep in the woods – the perfect spot to see the stars.